I hold a tangle of quick draws at my side and use my other hand to shade my eyes as I look up at the rock. I squint, scanning the line for anything that catches the sun, that shines, that’s metallic.

Hey dude will you check the guidebook for how many bolts this climb has? I can see two but there’s gotta be more. This thing’s like a hundred feet.

He flips through the guidebook and eventually stops. His brow furrows as he brings the page closer to his face and laughs a little, letting out a single “ha”.

You’re right. There are more. His scabbed finger points to the route description. Three bolts George. 90 feet.

I look down at my harness, a few stray quick draws still hang from my gear loops after cleaning the previous climb. I set the bundle of gear on a small rock, and my stomach telescopes as I remove all but five quick draws from my harness. Suddenly I crave the heaviness on my hips of a full, noisy rack.

Hopefully there’s a bolted anchor up there. Otherwise you’re carrying two too many draws–so much extra weight! He laughs again, this time louder.

I appreciate his joke but also become aware that it’s threaded with a serious warning: this climb is run out. Like, really run out.

I got it. It’s a 10c. I convince myself that I’m doing a good job of appearing fearless.

Alright. Have fun. I got you. He squeezes the carabiner with his hand and its gate doesn’t open. Locked and loaded, he says.

This climb marked the first step in my ongoing quest to understand why everyone hates climbing in Joshua Tree.

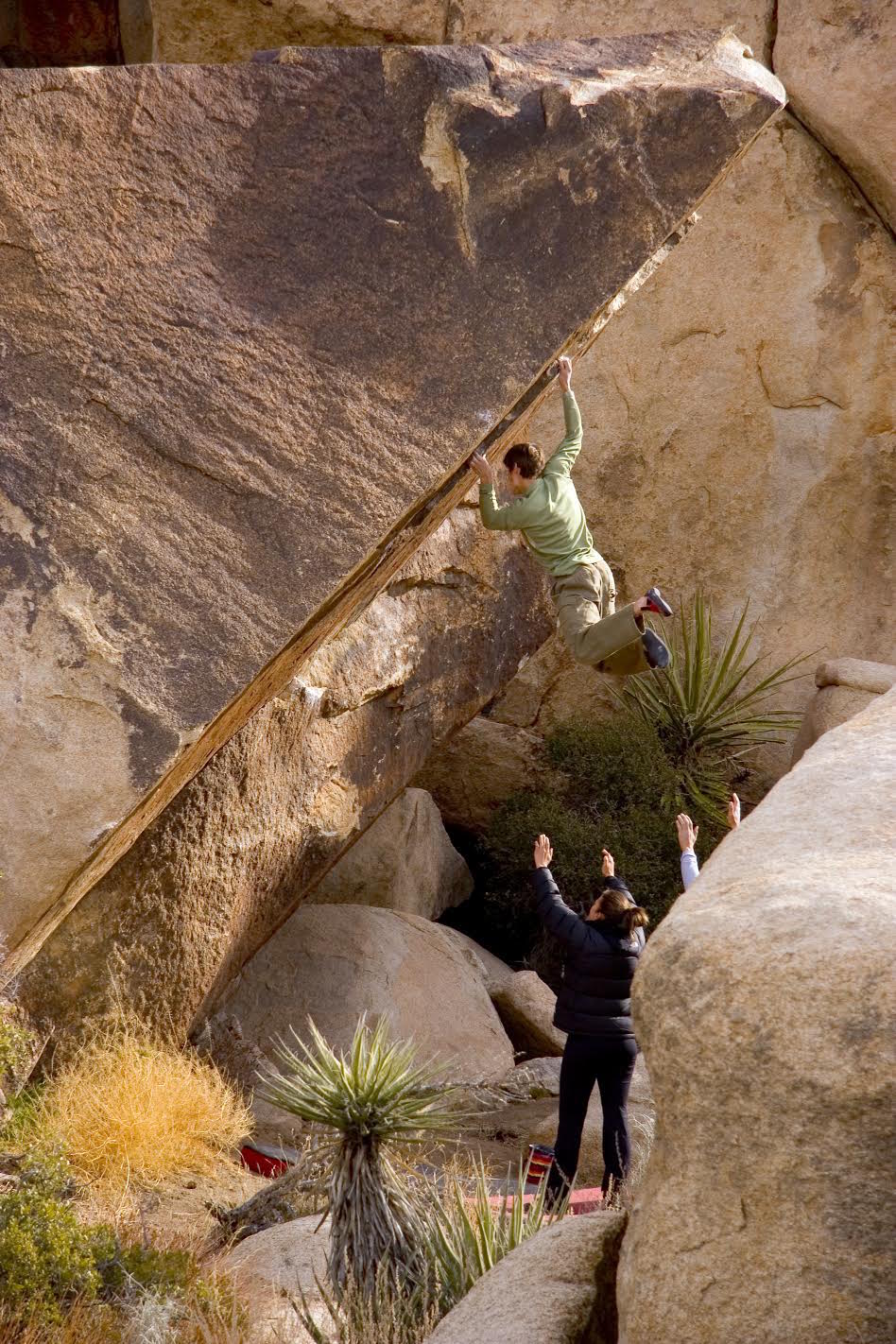

I know very few people who actually love the climbing in Josh, and they tend to either be 1. old men or 2. a little weird. Usually they are both of those things. Rarely are they 25-year-old females, and rarely are they professional climbers, but two of the people who I know that are Josh-lovers fall into those categories. I’m talking of course about me and my boyfriend. He is the professional climber:

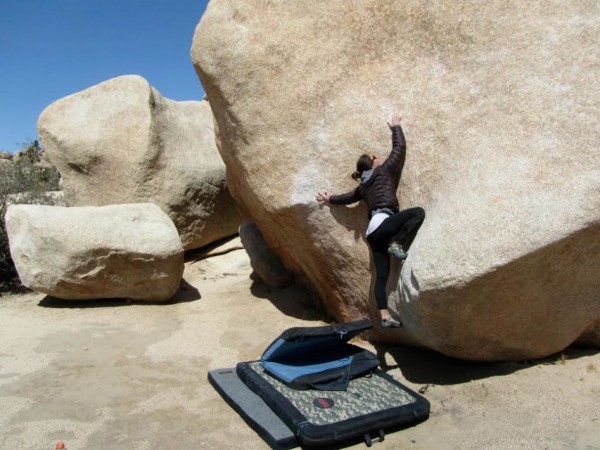

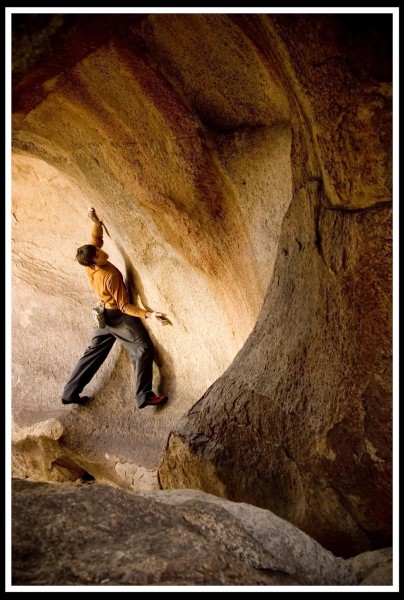

And this is me:

So, according to my above proclamation, since neither Ethan or myself are number 1’s (old men), that must mean that we are number 2’s (weird). Maybe so. But all of this really well-researched science and math doesn’t answer my question or help me fully understand why Joshua Tree is, arguably, one of the most hated climbing destinations in the world.

Maybe hate is a strong word, but it does say this on one of the first pages of the guidebook: some climbers hate Josh. And I believe it. Even before I had been to Joshua Tree myself, I heard horror stories of crazy accidents, top rope panic attacks, and grown men crying on 5.9. These were the kinds of things I was told whenever I asked someone if they wanted to go down there with me. Or, they would rattle off a long list of excuses: the boulders are too high and the routes are too short, the climbing is too spread out and we’ll probably get lost, the cracks aren’t splitter and the sport climbing is too run out, it’s always windy and driving down I-5 sucks. Oh, and everything is sandbagged.

This is usually the point in the conversation when I say, yeah, you’re totally right, so when do you wanna leave?

What’s even more surprising than Joshua Tree’s bad reputation is the lack of climbers who have actually been there. Even well-rounded and well-traveled climbers don’t seem to make it out to Josh these days. I don’t know why.

It took some convincing (babe, my Dad has a house in Rancho Mirage with a hot tub) and a little guilt-tripping (I’m sick of sitting on the valley floor while you climb El Cap) to get Ethan to agree to a Joshua Tree trip. I’ve never roped up down there, he said. Only bouldered. But I do love it, it’s probably my favorite place for bouldering.

Cool. Good answer.

As we drove down I-5, I told Ethan the story of the 90 foot line with 3 bolts that I climbed a few springs back. What I remember the most from that climb was an overwhelming awareness of not having the option to fall. That was a feeling I hadn’t experienced before. Even on multi-pitch trad climbs, highball boulder problems, or somewhat run out sport routes, falling is never ideal, and you might even get hurt, but it’s still a reasonable last resort. But on many of the climbs in Joshua Tree, falling is out of the question entirely because of extreme run outs, tall boulders, or very bad terrain/landings.

Uh.. we got you bro?

So if falling is not an option, this causes a few other things to occur. First off, if you want to project something (ground up), the option to fall needs to be available. Onsighting is simply what has to happen on most routes in Josh, and this pisses people off. Onsight climbing is just not of this time. These days, climbers like to try things over and over again in a way that is relatively safe (see: Iron Man Traverse). Most of us like to climb routes that are at or even way past our physical limits, and often in Joshua Tree that would not be considered projecting, it would be a death wish. And then there is, of course, the massive amount of fear that comes along with mandatory onsighting.

And then, there are the grades. You’re a responsible adult so you conservatively decide to get on a 5.10 because hey, you one hung that 5.12 in the gym last week. But then all of the sudden you find yourself trying really hard. And you’re about half way up that 90-foot climb and you’ve clipped one draw. Now you’re scared. The next section is completely blank. The next bolt is just a glimmer in the distance. So you quietly but most definitely proceed to freak the hell out.

But on second thought, maybe it isn’t the grades. I honestly don’t feel that Joshua Tree is sandbagged. It’s the climbing. It’s like nowhere else. Spending hours in the gym won’t help you. I don’t think you can train anywhere but Joshua Tree if you want to climb well in Joshua Tree. Unless you’re Ethan, then you can onsight things like Equinox without ever having roped up there before. But I’m not talking about him. I’m talking about us, the common folk.

The climbing mimics the desert landscape upon which it is set. It’s exposing and airy. There is nothing straightforward or easily fathomable about it. You’ll look up at a move and deem it impossible, but then once you try, once you just start to move, the sequence starts to unlock. You must be creative. Even what appears to be a straight-forward crack can be broken, varied, and inconsistent in size.

This causes some pretty obscure body position and movement.

The shapes that your body must take to move on these rocks blatantly resemble the iconic Joshua trees that give the national park its name. This creates movement that is much different from that of the more favored climbing destinations. It isn’t flashy like the overhanging jug hauls at the Red, it’s not glorious like the water-polished big walls of Yosemite, and it’s definitely not sexy like the straight-in jamming of Indian Creek splitters.

All of this tends to make people a little angry.

But this is exactly the kind of climbing that we need to be doing. The overhanging glory jugs, the lowball traverses, the straightforward splitters–these things are all good, and they should be climbed, but I don’t think we learn half as much from them. The kind of climbing that actually teaches us lessons of value, about our ego and how to be honest/kind/all that other good stuff, is the climbing that’s bold, thought-provoking, and humbling.

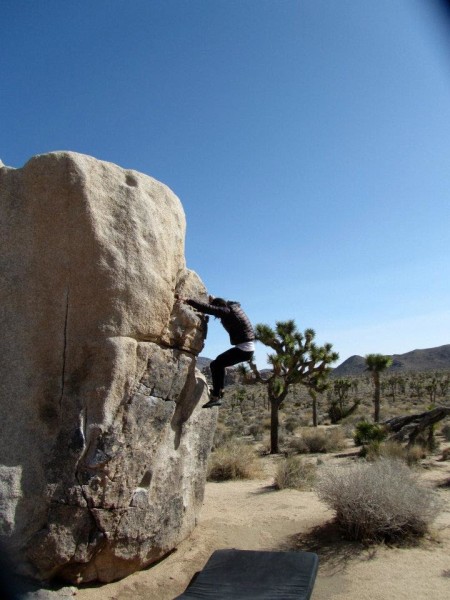

Can’t be too cocky when you fall off a v1:

I’m a yoga teacher and a bay area native so I’m a sucker for this kind of stuff.

My fingertips won’t stop sweating. I slowly reach behind my back to dip my hand in my chalk bag, praying the movement won’t cause my smeared feet to blow. One draw clipped, 20 feet below. After ten minutes of attempted crimping, I finally accept that I do not have any hand holds. My breath is rapid and choppy. Just climb, I say out loud. This is my only option, so I start to move. One foot and then the other. Pushing with my hands instead of pulling. Trusting my feet and breathing like a yoga teacher would. After a few shaky moves, I start flowing and the climbing feels like its 5.10c grade. I am no longer under the control of thoughts about the rope, bolts, or lack of quick draws on my harness. I just climb. I climb to the top.

‘Free’ is a good word to describe the way climbing in that desert makes me feel.

So, if I may leave you with my humble opinion: go climbing in Joshua Tree. Get scared. Flail on 5.9. Wish you were in Indian Creek. Make sure that cute girl knows you send 5.12 in Red Rocks. Get lost. Round up ten crash pads to try a v3. Get super annoyed by the wind. Hike for an hour to do one climb. Hike back to the car because the first gear is 20 feet up. Don’t project. Don’t fall. Don’t have any idea how to do Stem Gem.

This is the kind of climbing that our community needs: the kind that humbles us, that makes us brave, that makes us less of an asshole when we get back home.

See ya in the desert!