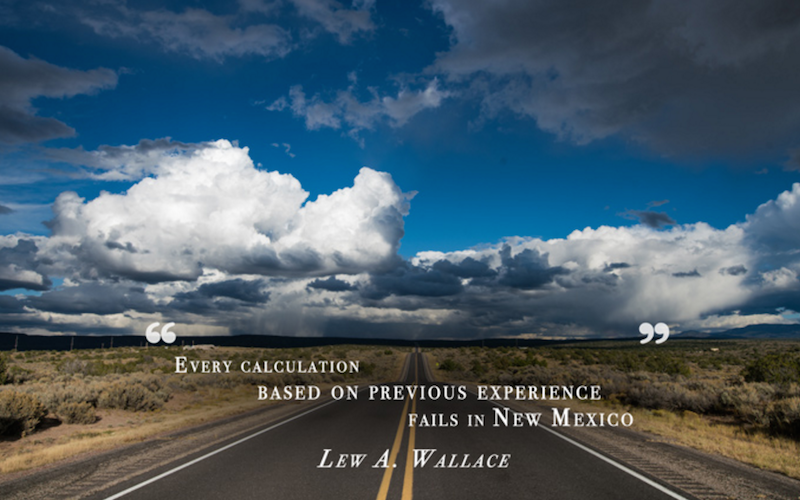

Exotic Locales, No Passport Required

New Mexico is nicknamed The Land of Enchantment, and climbers may be familiar with a particular tower that fell under the spell. But aside from the remote and mysterious Enchanted Tower, and the fact that one must pass through during the annual Hueco migration, New Mexico is almost entirely off the itinerant climbers’ collective radar.

Put simply, New Mexico is not on “the circuit.”

That’s about to change.

Roy and Not Roy

Folks, if you’ve been down with The Proj for a long time, you may recall a post from Spring 2014 excitedly showing pictures from Roy and La Madera. In fact, if you are an InstaStalker of some of the professional powerhouses like Jimmy Webb, you may have seen that Roy already has a handful of excellent high-end boulder problems. You may not know that there are already more than 1000 problems established and the potential for 1000s more.

Roy is not a secret. Noah Kaufman talked about the place almost 10 years ago. William Penner, the first guy that we know of to ever boulder in Roy, reckons the rock quality and number of quality moderates as well as hard test-pieces, already puts Roy in the “world-class” category. In fact, the tip of the Front Range spearhead has been probing these canyons for a while now, but for the rest of the estimated 950,000 climbers* (*my own personal estimate) who live on the Rockies’ eastern slope, Roy’s lack of guidebook and trademark problems make it a less appealing destination than the car-to-boulder trek across the Rockies to Joe’s Valley.

But Roy is not what brought us back.

Ortega Fall

There is a town in north New Mexico. Eric Bissell brought us here after a day spent in Roy. He promised a wild and largely undeveloped zone with some of the craziest rock in the world. “It’s like climbing on marble statues,” he said. Now, marble statues don’t normally make for good climbing, but know your sources: Mr. Bissell is a climbing ranger in Yosemite Valley. He ain’t no dilettante. The man knows what good rock is.

We drove to La Madera and hiked through what felt like an outdoor museum. If you asked an old hippie from Taos to sculpt an impression of an ideal boulder, you might end up with something like “Too Good To Be American.”

What really hooked me was when Eric pointed to a mountain in the distance. “That’s Ortega West,” he said. “It’s covered in the same rock as here, but it goes for miles. The locals have barely scraped the surface there.”

And that’s the moment that spending a season here became a very urgent priority.

No Locusts

“Human beings are a virus,” Agent Smith famously proclaimed in the documentary The Matrix. We have a tendency, thanks in large part to an economic model that emphasizes growth for its own sake, to range widely and exploit resources. We’ve always done it, and climbers are guilty too. Joe’s Valley, another remote desert bouldering venue with stunning lines and steep hillsides, is badly in need of a facelift. If nothing is done, we will soon see classic boulder problems rolling into the road thanks to erosion.

Historically, climbers in general and boulderers in particular could be partly excused for enjoying the rock in the moment without thinking about the future. They could reasonably conclude that the lack of popularity of the sport itself, coupled with the middle-of-nowhere nature of many climbing venues, would result in only a handful of visitors each year.

We now have ubiquitous video recording, fast internet, and hindsight. Ergo, we no longer have ignorance to exonerate us. “If you film it, they will come.”

We have the power, with our cameras, to shine a light on this special place. But we have a responsibility to think about our actions not just in isolation, but in connection with the past and the future. And so we ask ourselves, if we help spread awareness of this incredible place, what changes can we anticipate, and can the area handle those changes?

Inviting the Crowds

Developing a climbing area is much more than scrubbing rocks and naming routes. If we think it’s good, and we post about it, then others will follow. It’s the nature of our tribe, and it’s frankly one of the coolest parts about being a climber. We are all psyched for one another; it’s all about shared experience, not exclusivity or competition.

But we have been careless in the past. Our excitement about the climb takes over, and we must do it now. We’ve been planning this trip for months. We want our friends along even if the landing zone doesn’t have enough space. We spray about how good a place is without mentioning the environmental concerns, and we begin to love a place to death. It’s a very common story. The Conscious Climber Project (CCP) is an attempt to change the paradigm.

But we have been careless in the past. Our excitement about the climb takes over, and we must do it now. We’ve been planning this trip for months. We want our friends along even if the landing zone doesn’t have enough space. We spray about how good a place is without mentioning the environmental concerns, and we begin to love a place to death. It’s a very common story. The Conscious Climber Project (CCP) is an attempt to change the paradigm.

The CCP is timely, as a Los Alamos climber, Owen Summerscales, has been compiling a guidebook to New Mexico bouldering. Not only is it beautiful (I’ve seen the drafts), but it is the first guide to NM bouldering to include most of the good stuff. This will immediately bring out the Santa Fe and Albuquerque climbers on the weekends, and Colorado is not far behind. I’m writing this from the parking lot to what will likely be the most popular of the Ortega areas, and I could be at Mile High Stadium in 5 1/2 hours. But right now, this place can’t handle more than maybe a dozen climbers a day.

The Conscious Climber Project

We are spending the season focused on four areas around the Ortega mountains. They are characterized by incredible quartzite rock, abundant moderates, and a wild and scenic environment. The local climbers have already done a good job establishing proper use patterns, and they have been very generous and welcoming to visitors. We have their support.

We will be releasing a series of videos, photos, and blog posts that will present some of the common issues that bouldering areas have, and how developers and early visitors can ensure the sustainability of these playgrounds. We’ll also be highlighting some of the many four-star lines that have already been done and that we plan to do, but, dear reader/viewer, you’ll have to put up with just a wee bit of Conscious Climber messaging before you get your climbing porn.

We will be releasing a series of videos, photos, and blog posts that will present some of the common issues that bouldering areas have, and how developers and early visitors can ensure the sustainability of these playgrounds. We’ll also be highlighting some of the many four-star lines that have already been done and that we plan to do, but, dear reader/viewer, you’ll have to put up with just a wee bit of Conscious Climber messaging before you get your climbing porn.

It’s a special opportunity for us to witness, document, and participate in the development of such an enchanted place. As we’ve always shared our stoke with you, from Birthday Challenges to French Presses to Walmart parking lots, we can’t wait to show you these insane boulders. But more importantly, we can’t wait to show you how much power YOU have to make sure your grandkids can enjoy the same feeling of enchantment that we feel right now.

By The RV Project.