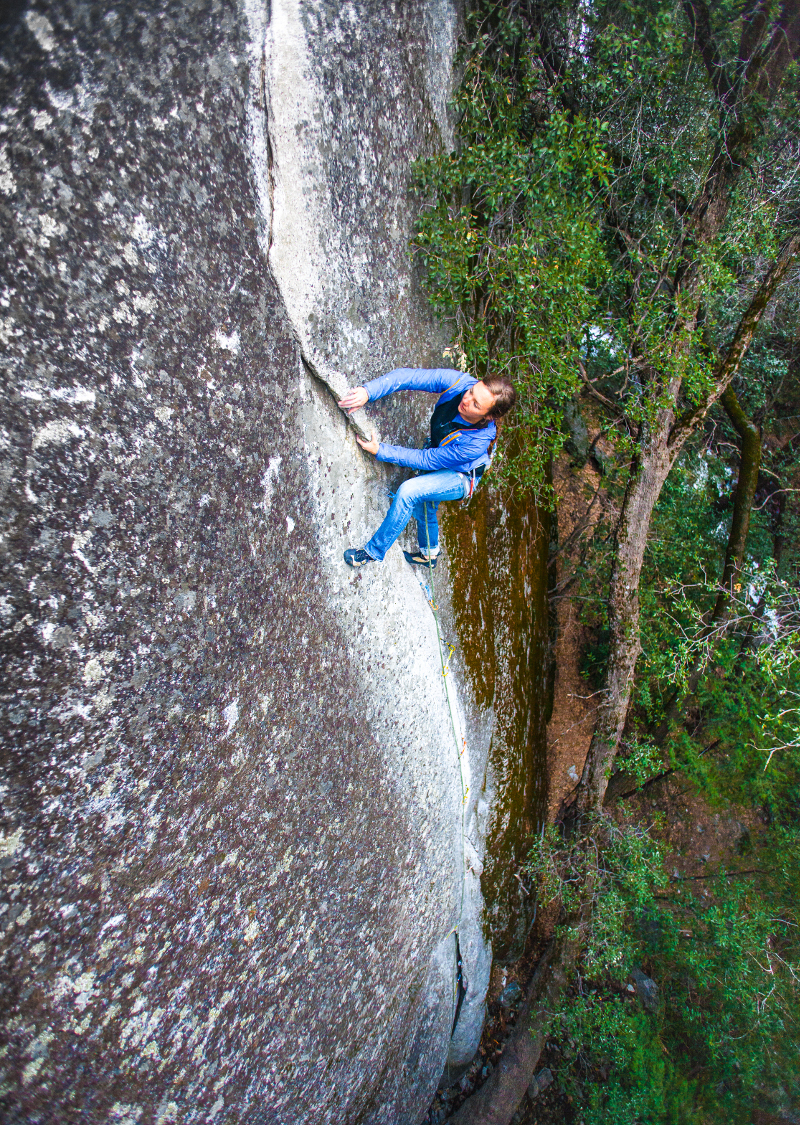

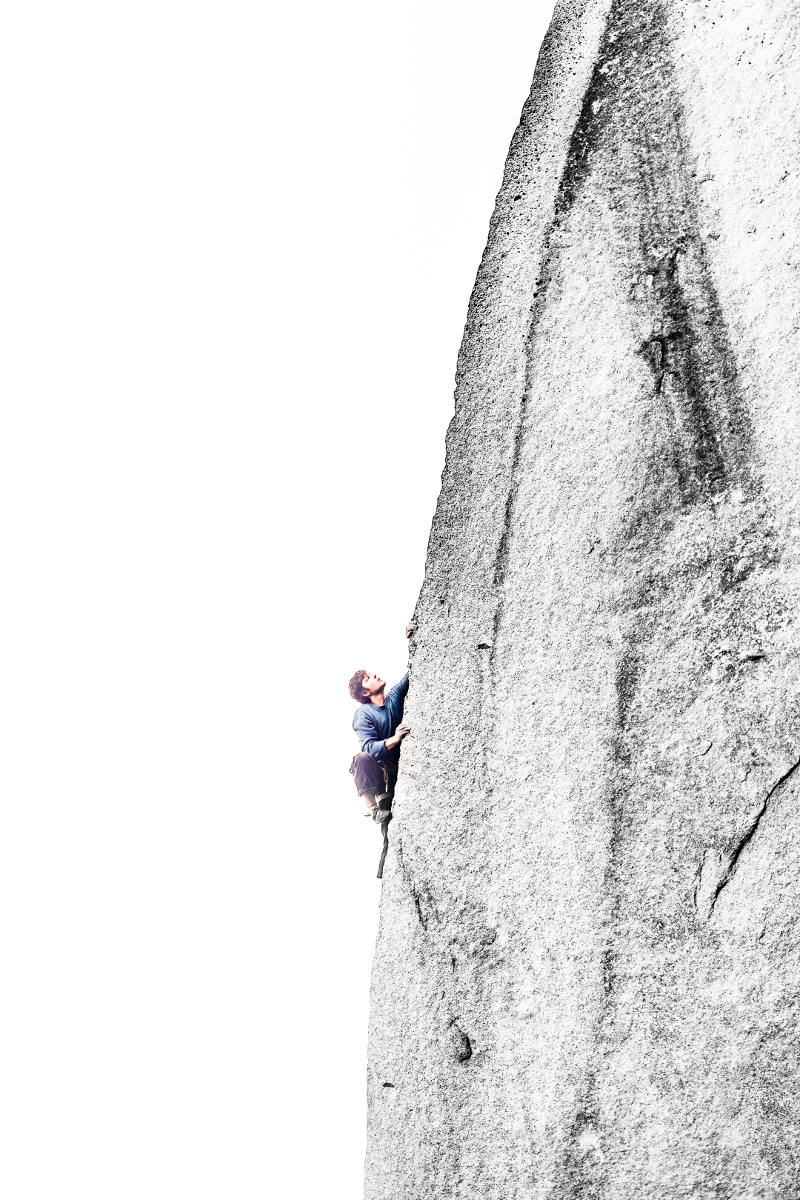

Dean Fleming was born and raised in Sonora, CA, the gateway to Yosemite Valley. Once the youngest certified professional climbing guide in the country, he eventually combined his love of writing, photography, earth science, and rock climbing into a career of sharing his stoke and expertise through publishing. Dean is the author of the Columbia Bouldering Guidebook and the founder and editor of California Climber Magazine. In this series, he’ll be sharing a taste of some lesser-known, high-quality climbing areas in our favorite state, plus how to take care of these special places for years to come.

Words and images by Dean Fleming.

Yosemite Valley boasts quality and quantity in equal measure, but it’s the park’s distinct and colorful reputation that sets it apart as a must-visit location for thousands of climbers. Glorious tales have been published about Yosemite’s Golden Era and the subsequent reign of the Stonemasters. The colorful manuscripts and classic images of 1960s and 1970s helped the National Park grow into a sought-after destination. At the turn of the century a new study of Yosemite prodigies continued to inspire the masses. With each passing season Yosemite’s social circle grows larger and the community continues to break boundaries on the tallest walls and smallest boulders in this truly historic climbing arena.

I was born in Sonora, California, about 50 miles from Yosemite National Park, and began climbing on Sonora Pass in 1995 at the age of 10. A guidebook for Sonora Pass would not be published until 1998, and so those first few years were spent in an adventurous fashion, gazing up at the cliffs and guessing which way to go and how to get down. We didn’t know if the climbs we ascended had been done in the past, if they had names and grades, or if others thought these climbs were cool. And we didn’t care. We climbed because it was fun, and because in a town as small as Sonora, there was nothing better to do.

On those first few trips to Yosemite, after struggling up some unnamed, 30ft-tall butt-crack at Swan Slabs, I’d sit in the meadow with my dad and watch folks rack up for routes like The Nose, Mescalito, and The Shield on El Capitan. I had dreams that, one day, I too would be gearing up at the base of El Capitan for an epic ascent. I thought about graduating high school, living in Yosemite full-time, and falling in line with the new generation of Yosemite climbers. But years passed, and then decades, yet I continued to spend my days cowering in the bushes, close to the ground, scraping dirt and moss out of the one-star climbs at Yosemite’s most insignificant crags.

Yosemite is Mecca for climbers around the globe, but the area’s popularity is not always welcoming to those who seek solitude in the forest. The Valley’s classic trade routes are often jam-packed with visiting climbers. On a busy summer weekend it is not uncommon to find up to ten parties in line at the base of a three-star climb that is close to the road. This heavy traffic buffs the footholds, greases the handholds, and wears down fixed anchors: all large contributors to Yosemite Valley’s reputation for polished rock and sketchy descents.

Although the classic trade routes in Yosemite are meticulously mapped, blogged about, photographed and publicized, the smaller crags in the Valley still beg to be explored. Occasionally you’ll find a bit of dirt and a few bushes growing out of the cracks, but the one-star climbs in Yosemite can be as good as any three-star climb at North America’s other granite climbing destinations. The rock on these one-star routes is often textured, featured, and solid. With sticky footholds and often perfect protection, the climbing found on Yosemite’s obscurities can be excellent; and the solitude found here can provide some of the most rewarding climbing experiences in California.

If you visit Yosemite Valley, you should tackle the trade routes and classic lines that made this area famous. You should do routes like Royal Arches, Nutcracker, Serenity Crack and the Central Pillar of Frenzy, and when you’ve honed your granite climbing skills and rope systems, you should move on to climb bigger routes like The South Face of Washington Column, The West Face of Leaning Tower, The Regular Northwest Face of Half Dome, The Nose and The Salathé Wall; for perhaps nowhere in the world boasts higher quality climbs of equal length and difficulty. But if you have the time, and you have the desire to explore a wide variety of granite crags and climbing styles, it’s well worth the effort to step off the beaten path and explore the lesser-known areas found in the back corners of Yosemite Valley. The climbs listed below are just a few of the hidden gems of Yosemite, and they foster a sense of adventure and promote the idea that both visitors and locals alike can still find a lifetime of exploration, solitude, and adventure on the walls and boulders of California’s most iconic climbing destination.

Peruvian Flake (5.10a)

Located near the base of Royal Arches near the Ahwahnee Hotel, Peruvian Flake should be every aspiring Yosemite 5.10 leader’s first 5.10 redpoint or onsite. While the thin fingers section does require a few tiny cams and can be intimidating, it’s very short and is followed by a glorious 50-feet of incredible 5.8 climbing.

The Flake (5.10b)

The Flake is the steepest 5.10b pitch in Yosemite Valley—it’s also an incredible sandbag. But it’s short and well-protected and stays dry in a light rain. Located on the Knobby Wall near the Cookie Cliff—an amazing 45-degree overhang with diorite jugs—The Flake is an often overlooked challenge that warrants a visit.

Spinal Tap (5.11b)

Spinal Tap is located directly off the highway, yet is surprisingly hard to find. While often ignored, this knife-edge arête is one of the finest technical bolted face climbs in the region. The lower portion of this laser cut corner invites climbers to move past the first three bolts on positive holds. Above, an otherwise featureless slab forces would-be ascentionists into a demanding series of arête slapping maneuvers while fighting a relentless barn door on diminishing footholds.

Little Wing (5.10d)

Three excellent routes can be found at the Little Wing Buttress, but the area’s namesake route Little Wing (5.10d), is certainly the star of the show. Little Wing starts with a locker finger crack that is augmented by a few half-inch edges that beckon to be used as footholds. At about a third of the way up, an obvious three-foot roof can either be jammed past or hero lay-backed on a huge in-cut, side-facing jug. The remainder of the route sports technical finger-locking, hand jamming, and a few tricky sequences that lead to a scenic two-bolt belay.

Highway Star (5.10a)

With an exceptionally short approach from Highway 120 and convenient access to the summit of the formation for top-roping, Highway Star’s short but powerful sequences have been used for running laps and end-of-the day warm-down sessions for generations. Highway Star is a mere 50 feet in height and may be considered moderate at 5.10a, yet this small route is steeper than it appears and has been known to surprise unsuspecting leaders with its strenuous sequences.