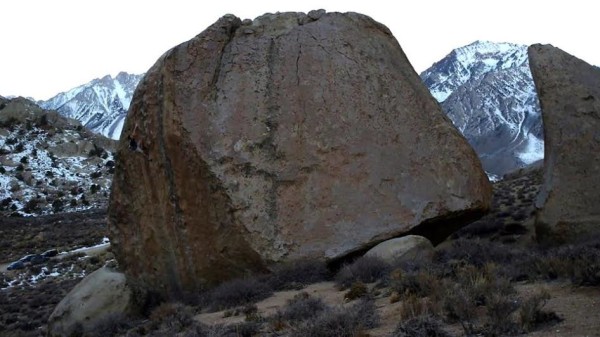

It’s summertime in Berkeley. I sit in the hot living room of my friend’s apartment, the overhead fan creates a weak breeze. We are watching Reel Rock 7, I’m missing Bishop like crazy and getting inspired and terrified by Alex Honnold’s first ascent of Too Big To Flail: a micro-crimpy, foot-work intensive highball in the Buttermilks. I start to wonder if “highball” is an appropriate term when talking about a climb that’s 50 feet tall.

Well, that’s never gonna be repeated. Joe tilts his beer back, finishing off the last sip.

Someone will do it, I say.

Oh yeah? Who?

Someone. I don’t know who. Maybe we don’t know their name yet, I reply.

A year and a half later I find myself shlepping crash pads and encouragement up to the Luminance boulder so that professional climber, Ethan Pringle, and some 19-year-old Cal student named Steven Roth can try to bag the third and fourth ascents of Too Big To Flail.

The afternoon before, the pair threw a rope down the thin line of the boulder’s North face and took turns sussing out the moves. They shouted words of positivity to each other from the ground as they broke the climb into different sections. Their beta was vastly different for some moves and identical for others, but neither Ethan or Steven looked like they were having to try all that hard to pull the sequences. It was obvious to everyone that for them, sending Too Big would mostly be a matter of just going for it.

Neither of them are strangers to highballs–Ethan has ticked countless airy Buttermilk classics including Evilution (Original Exit), This Side of Paradise, and The Beautiful and Damned. As for Steven, on the weekends when he doesn’t have to teach Intro to Climbing Clinics at Berkeley Ironworks, he quietly climbs some of Bishop’s proudest lines like Ambrosia, Rise, and Footprints.

I reach into the bottom of my pack, fishing for my headlamp. The sun dropped behind Mount Tom an hour ago. Ethan lowers Steven to the ground after his last burn, he unties as he looks up at the green and yellow lichen-streaked face.

Cool, Steven says. I’m gonna do this thing tomorrow.

Nice dude, Ethan says. I can tell Ethan isn’t sure at this point if he’ll go for it without a rope, otherwise he would have said so.

After dinner we drive to the Thunderbird hotel. I’m wondering how it doesn’t smell like feet or a barn or a dumpster considering there’s four boys in here. We huddle around a laptop and watch the teaser footage from Alex Honnold’s latest solo of El Sendero Luminoso in Mexico.

Holy s—, Ethan says.

Holy f—- s—, I say.

This is awesome. But he’s fine, he’s on a slab, Steven says. I shake my head and laugh a little.

I envision the eve of a big, committing send to go something like this: eat a salad, do yoga, mentally rehearse the moves on the climb. Ethan is pretty much doing that, minus the salad, but it’s clear that the route is on his mind. He’s still undecided about whether he’ll go for it ropeless, wondering if he’s ready, if it’s worth it, if going for it means he’s being reckless or impatient.

I’ll have to see how it goes tomorrow. I want to do it clean on a rope a couple times before I decide, Ethan says.

But for Steven, this night is different. He’s putting off doing his thermodynamics homework by showing us videos of cats with very short legs. You guys have to see this, Steven says. They’re called dwarf kittens! They’re soooo cute. Oh wait! Type in “munchin scurry!” It’s just a whole page of dwarf kitten GIFs! Anthony and I exchange a look and laugh immediately. No seriously! You guys are gonna love this. I want one as a pet so bad!

Wes puts his palm to his forehead.

Come onnnnnn, Steven says, drumming his fingers as the page fights to load with the weak internet connection.

There are no thoughts of the climb, no reconsidering his decision to go for it tomorrow, no wondering if he’ll pitch from the top, no phone calls made to acquire more crash pads. Tonight, Steven’s mind is on the homework he’ll have to do on the car ride back to the Bay and dwarf kitten adoption possibilities.

We wake up the next morning to mild, almost warm weather in town–uncharacteristic of February in the Eastern Sierras. Ethan and I head over to our friend’s house and grab several crash pads, we have to rearrange them a few times to make them all fit in the Honda Element. After the bumpy ride up Buttermilk Road, we park at the Birthday boulders and sit in the car for a moment. I look out at Buttermilk country. It’s bright and sunny just like it was in Bishop, but there is evidence everywhere of strong winds–a whooshing sound coming from the car windows, crash pads being lifted up and carried into the sage brush, some dude running after a plastic grocery bag up by Iron Man Traverse.

Sending temps, Ethan says to me. This is the first time he has even slightly suggested that he may be considering going for Too Big To Flail at some point today.

We meet up with the rest of the group and drive over to the Luminance parking lot. Four cars, about 15 crash pads, eight people to carry them. We strap pads together and hike up to the boulder, confident that we’ll be seeing at least one attempt of one of Bishop’s proudest lines. The wind sprays sand into my face and my crash pad catches a gust. I fight to keep my balance, to stay standing.

Ethan and Steven rope up again. This time they try the route starting from the ground on top rope, trying to link the entire climb without any falls. They both successfully do so about three times. In the background, the rest of us jabber on about mindless subjects like poop and protein powder, assuming Ethan and Steven would each spend another hour or so top roping. Little do we know that Steven is about to go for it.

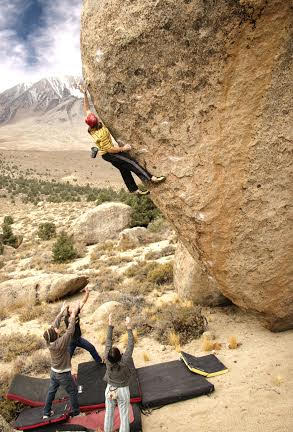

We duck behind boulders so we’re out of the photos that Anthony is shooting from up the hill, and as Steven takes off his harness we’re all still arguing about how many times a day a healthy person should poop. The boys say three, minimum. Heather and I say once. But then he chalks up. He looks up at the line. He climbs up the small boulder to reach the start holds. As soon as his feet leave the ground, we are all quiet for the first time the entire weekend. I hear Mike swallow hard, he turns away. I can’t watch this, Mike whispers. My stomach tightens as Steven balances through the opening sequence.

The thing I remember most was the silence. How even scratching the back of my hand felt disruptive.

The wind starts to pick up as Steven comes into the rest. He adjusts his feet, reaches behind his back and dips a hand into his chalk bag. A stream of chalk twists into the wind. He reaches far to the right for the next crimp, his left hand follows. He climbs out of the rest. The higher he climbs the stronger the wind grows. He finishes the section of three long moves in a row, the wind is now coming in steady gusts, strong and unannounced. His signature Jimmy Neutron hair is matted down to one side. His Ironworks Belay Staff hoodie puffs up like a sail. He’s about thirty-five feet from the ground.

I wonder if the wind will blow him off the wall. I wonder if he realizes how committed he is right now. I wonder if he’s scared. I wonder how he climbs something this tall, this hard, in these conditions, with seemingly no consideration of not climbing it.

Soon, he’s pulling through the delicate moves close to the top of the boulder. His pace is faster than it was through the first three quarters of the climb but he looks secure and steady. A few crimps later, he gains the last hold, a huge jug on the boulder’s lip. Steven stands on top of the boulder that Bishop’s hardest and highest lines call home, and he has just done the third ascent of Too Big To Flail. We all hoot and holler and clap, abruptly breaking the silence. Steven smiles, he’s quiet and stays atop the boulder for just long enough to pose for a celebratory picture before heading over to the down climb.

The boys exchange high fives with Steven, I hug the everliving daylights out of him. Eventually we quiet down from the excitement of the send, and soon it becomes apparent to everyone that it’s time for Ethan to decide if he’s going to go for it or not.

I sit next to Ethan, we both look at the climb. It starts to rain, steady for just a few minutes and stops. Off and on. The weather is good and then bad. The wind blows and then its calm. Every few moments, Ethan takes a deep, loud sigh. That’s when you know he’s really thinking hard.

How do you feel? Gonna give it another lap on TR? Or are you ready now? I ask.

I don’t know. Honestly, seeing Steven do it doesn’t really make super eager to climb it. This is really serious.

Yeah. Well, just go have fun. But be safe, I say. Thanks, he says. I’m gonna run up the hill to stay warm. Ethan takes off up the gravely slope. We all know the actual purpose of this run is to make his decision.

His struggle is this: he knows that he is more than physically capable to do this climb. But is now the right time? He has every excuse not to go for it today–the wind, the rain, his feet hurt, he’s getting cold, he can’t feel his fingers, maybe he needs more crash pads, maybe he should rehearse a few more times on top rope, maybe he should just call it good and find another project because crimping isn’t what he’s best at anyway.

The sky is inked with dark rain clouds as the afternoon storm rolls in. Ethan jogs back down the hill. He walks to the base of the boulder, slips on his shoes and straps his chalk bag to his waist. He climbs up the small boulder to gain the start holds, leaving his harness sitting on the ground.

He’s going for it.

He exhales audibly and pulls on to the face. Slowly he shifts through the first moves, deliberate and slow. He pauses sightly after each move. After a few moments, he makes it to the rest.

Ethan stands in the rest for a long stretch of time. He takes off his hat and it slowly flutters to the ground. He presses his fingers to the back of his neck as to warm them, shifts his weight left and then right, takes several full breaths. After a few minutes he looks up at the rest of the climb. He chalks up and keeps climbing.

Traverse right to a good hold. Pause. Exhale. The insecure slopey foot move. Pause. Move to gain the better foothold. Big move, big move, big move. Exhale. Getting close to the top. 5.12 slab climbing section. Trust. Move. Breathe.

He climbs with such great attention that he notices small raindrops landing on his next hand hold.

40 feet from the layered crash pads, he reaches high and pauses with his palm just skimming the rock, mid-move. He is still for a full breath. My jaw clenches. He finishes the move, balances through the finishing section, and soon his hand is on the line’s only jug. The silence breaks again. YEAH! We yell. Ethan rocks over the lip of the boulder, screams and puts his arms into the air. The wind pushes him back forcefully, he looks alarmed as he regains his footing. He yells down to us. I almost just got blown off the top!

Ethan smiles so big that his eyes squint. He takes his time on top of the Luminance boulder, shouts some more, but eventually the strong winds persuade him to down climb.

I remember the drive out of the Buttermilks that day, how I looked out at the Whites and thought about both of the boys up there, how they each stood on top of that boulder in such different ways. Everything was varying–the mental preparation, the struggle or lack of struggle with the decision to go for it, their attitude about climbing something that committing, the way they climbed, their reaction to sending. But it was the same climb, the same day, they took almost the same number of top rope rehearsals and they both eventually sent.

It worked because both Steven and Ethan trusted their own unique processes. There was no question in either of their minds that perhaps they should be going about this whole thing more like the other one. They weren’t acting like anyone else up there. And that is why they both ended up sending one of the tallest, hardest boulder problems in the world, Too Big To Flail.

By: Georgie Abel. All photo credit goes to Georgie Abel unless otherwise noted.