By Mark Melvin. All photos by Mark Melvin unless otherwise attributed.

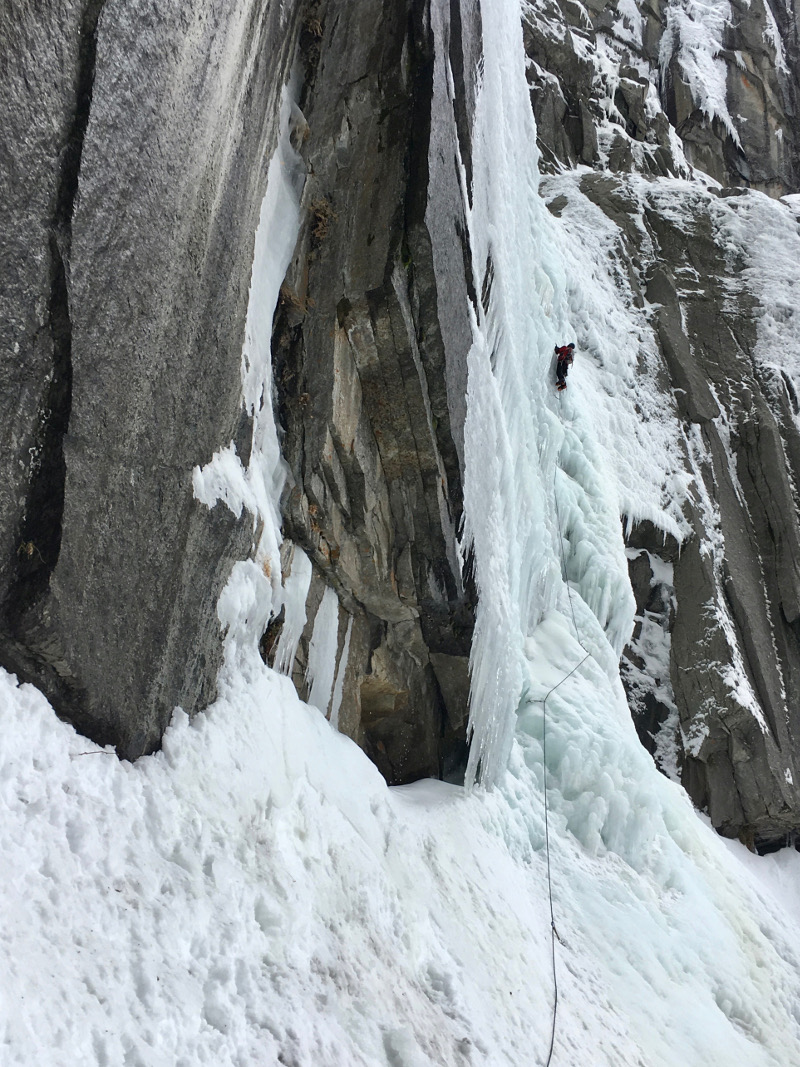

Widow’s Tears is not just a long ice climb. Its 1,000′ approach, multi-hour post-holing off-trail descent, and ephemeral nature make it an adventure climb, in which mountaineering skills are as valuable as those for technical ice. Because it lasts only a week in the rare years it forms, conditions are unpredictable and unknown prior to the climb and likely run the gamut over the years—either it’s forming or it’s falling, there’s nothing in between. The setting is spectacular: an amphitheater of rock, with the waterfall cascading from the back right corner.

I’ve wanted to do Widow’s Tears for decades. California is constantly in drought, providing little snow pack in the high country to supply water to seep and freeze. But not this year. I figured with an above average early rainfall, a cold snap could make it form. In mid-February we experienced just that. My son Daniel and I got our gear ready, rushed up to The Valley, and…nothing.

Interestingly, most photos of Widow’s Tears show no ice on adjacent rock, kind of like Canadian-style, all-winter-long falls, the ice in sharp contrast to rock nearby. Not this year. We had ice all over the place. There was 1” ice in a thousand gullies in Yosemite. But not enough to form the Tears, or even Silver Strand, which forms far more readily. And then it warmed up. Since we were there, we decided to scope out the approach as a full family: Debra, Daniel, and I slogging through deep snow the wrong way up. Below see details for the right way up.

Three days later I went back to The Valley. I had heard it might be forming even as temperatures were warming. On February 23rd it looked just thick enough. I asked Daniel to come back up, cancelling work for the week. He arrived the 25th and we planned to do the route the next day.

High up I could also see holes with water, but it looked as if ice there could be avoided by going right. We decided to go for it.

At 3am on the 26th, it was already 45˚ in El Portal. We were warm even before we started, which made us feel there was little chance at best. It took us until 4:45 to leave Bridalveil Falls parking lot. We walked the quarter mile up the road to the old highway, donned some technical snowshoes I had borrowed from my good friend and multi-epic partner Tom McMillan, and started hiking. Five hundred feet past the second drainage we headed up into the woods. We cleared the woods in dark, tromped up the snow slabs into the alcove and up the snowfield to the rock. Water was running under a lot of the ice, but it looked thick enough. High up I could also see holes with water, but it looked as if ice there could be avoided by going right. We decided to go for it.

Pitch one was easy, WI3. I hoped that one rope length would take us to the obvious ledge system; stupid optimism in play, although without it would we even be here? I belayed where the terrain got even easier.

The second pitch could be done WI4 straight up, but going left made it more like WI3, which we took. My first choice upward was halted as ice ran out beneath snow. I backtracked 20’ and went for another narrow wet gully with a tricky move or two leading to the large ledge. I’ve seen a bunch of photos in which there was no ice to the left of the easy entry falls. But I’ve also seen photos showing a traverse. Basically, if there’s a traverse in the climb there’s only one place it could be, and that is to get back right after veering left on pitch 2.

Our third pitch was deep snow for a full 70 meters, no protection available or required. I’ve seen photos where people traversed right over rock. This year the snow made this pitch super easy.

The rest of the route is 900 feet of various ice straight up under the amphitheater corner, which can be done nicely in four long pitches, the longer the pitch the better the belay stance. We had a 70 meter rope, and wouldn’t have needed an 80, but we stretched all of the last three. We had 11 ice screws on our rack, with 3 old backups in the pack for retreat, which with the long pitches we used. We took five cams and a couple stoppers, but never had an opportunity for any rock gear. Nearly all the ice we encountered was highly aerated, causing us to veer onto steeper ice to get decent screw placements. 700 of the final 900 feet are WI4 or WI5, depending on how “blue” the ice is, or how easily one can climb the middle of the falls where the water is running. A lot of accounts suggest short ice screws, where we really needed longer ones. I would suggest an assortment.

Nearly all the ice we encountered was highly aerated, causing us to veer onto steeper ice to get decent screw placements.

Probably the most common crux pitch was our fourth, or the first of this vertical section. It started off with an easy slab to cauliflower ledges before getting steep for 40’ of WI5, then easing off for a belay about 180’ up. This was the best ice on the route. Because it is a pinching point of the falls, it’s probably often the steepest ice.

By now all the walls around were sounding off, ice constantly falling, mostly small ice releases whose noise was amplified by the amphitheater. If unnerving, none of it was coming down Widow’s Tears, so we felt safe to continue.

The fifth pitch was easily as hard as the fourth for a couple dozen feet before easing off with a traverse left to an even easier ramp, ending on a big ice bump a full 70 meters out.

The sixth looked far easier than it was, with lots of rugosities, having a section of slightly overhanging WI5 ice of maybe 30’, also a full 70 meters to a point that we could see the last of the route, quite a bit less steep. As I set my sixth pitch anchor, Daniel yelled “ice.”

As I set my sixth pitch anchor, Daniel yelled “ice.”

I looked down to see him crouched into the wall and ice all over the place, having come from the left of the falls at the very top of the wall. Daniel said he wondered if this would do him in as he watched it launch toward him. The ice had come from the left, and fallen to his right, rupturing a part of the large knob he had just finished belaying from, causing water to start flowing out of the snow. In any case, he was alright and proceeded to climb the pitch. Daniel’s one of those partners, where, if you’re going to die freezing slowly on a ledge, you’ll be happy and joking as you do it. With little ice experience he took no aid and motored on up, fast, efficient, and fun to climb with.

The final, 7th, pitch was easy, WI3, ending in snow to the top. Thirty feet back is a poor little tree that I stretched for a belay, although a snow belay would have been plenty safe.

We started the first pitch about 7:45am and topped out at 4:45pm, hoping we had daylight to find a trail. Basically, we got lost for an hour or so and eventually came upon some snowshoe tracks. Figuring that anyone out there was going to the road eventually, we followed it as it wandered all around, up and down, having fun in the woods (fun for them, nightmare for us). Four hours later it finally joined a beaten snow path, where we turned right and slogged another two hours east.

I went up the next morning to retrieve Tom’s snowshoes. The whole amphitheater had been avalanching from the upper ledge, to the base, on down and over the slabs and into the woods. I watched and darted to the base to find only one snow shoe. Being more observant on the descent I was able to find two more in the debris. Guess I owe Tom a snowshoe. If someone finds one, I’ll send them the other.

I think the route probably only lasted in a climbable form for a couple days.

I think the route probably only lasted in a climbable form for a couple days. Because of its variety, the ice was really fun to climb. And the setting was spectacular. Other than the one ice fall, it wasn’t particularly dangerous, just adventurous because you don’t know what you’ll encounter.

Mark’s trip report has been reposted in full here. You can find the original post on SuperTopo.